EDITOR'S NOTE: The following is a first-hand account by CSR Mechanical Engineer and Technical Advisor Wolf Fengler, MSME on his trip to assist the HSB on the first phase of development pertaining to modern steam locomotion.

I could barely believe what I was reading - CSR President Davidson Ward had just emailed me to see if I would travel to Germany to take charge of the data acquisition phase of CSR's work with the Harzer Schmalspurbahnen, GMBH (HSB). In the months leading up to this email, CSR had been contacted by Department Head of Equipment Technology at HSB, Bernd Seiler, after which dozens of emails were exchanged concerning possible improvements to the HSB fleet of locomotives.

The popularity of the HSB meant that the locomotives are often being pushed up to, if not beyond, their designed limits. The oldest locomotives on the line, the 0-4-4-0T locomotives, known as "Mallets" are worked hard to keep their trains to the timetable, having the result of occasionally sucking burned embers from the firebed and starting lineside fires as the draft pulls cinders through inadequate spark arrestors.

Something had to be done.

Having traveled the world in search of steam, HSB Department Head of Equipment Technology, Bernd Seiler, became acquainted with CSR Chief Engineer Shaun McMahon and knew that answers to many of the problems facing the HSB could be found in the work of L.D. Porta and his followers.

Over the course of several months, discussions between Bernd and the CSR team determined that 0-4-4-0T 99-5906 needed the most immediate help. In particular, the locomotive is underpowered and features a spark arrestor that not only retains most of the cinders in the smokebox but is also aerodynamically inefficient. Built in 1918 from designs dating to the late 1890's, the locomotive has a stack [RIGHT] that is engineered poorly and constructed inexpensively by shop forces many years ago when an earlier stack corroded beyond repair. This temporary replacement stack was once again coming due for renewal. The need to engineer and form a new stack opened the door for CSR to provide engineering assistance to HSB.

In further discussions with Bernd, it was found that a series of other, related, issues plague the 5906. The flexibility of the articulated design of the locomotive makes it well suited for the tight curves of the HSB network, but design deficiencies needed to be addressed if the 1918-built compound was to be able to keep up with the unprecedented traffic demands. Though lacking superheat, feedwater heating, and numerous other features essential to efficient steam locomotion, budgetary and other constraints dictated that initial efforts be focused on one area – the smokebox.

CSR determined that a combination of a custom-engineered Lempor exhaust system and Master Mechanic's spark arrestor would be the best way to bring immediate benefit to the HSB and to set the stage for further work. Of course, given the preservation-conscious nature of the HSB, the design work would be constrained by the need to maintain the original, historic outline of the locomotive.

By this point, perhaps you are asking yourself; what does a primitive, 1918-built German steam locomotive have to do with torrefaction, CSR locomotive 3463, and the development of modern steam?

Actually, more than one might initially think.

First, CSR's opportunity to work with the HSB facilitated our testing of critical data acquisition instruments and software on an in-service steam locomotive in advance of applying it to 3463 and to other advanced steam-driven electrical generators. As learned from the ACE 3000 project and other attempts employing modern sensing equipment, advanced sensors and steam locomotives have met with mixed results, so it was important to begin work in this area as soon as possible. Second, this research allowed us to gain experience with a functioning compound locomotive, the efficiencies possible with compound operation being critical to any new design steam power plant. Third, it gave our team its first opportunity to work together on a design problem. While our core group all have excellent qualifications as individuals and have been working together to frame and forward the technological focus of CSR, it is always important for an engineering team to solidify itself as a unit by rallying around something more than just theoretical concepts – all the better to do so before engaging in the much more involved work required for 3463. Finally, one of the attractions of the HSB operation is the diversity of its motive power.

The potential to improve an older locomotive in a historically-sensitive manner while allowing it to keep up with the demands of present day operations would assure its vitality and help preserve the unique character of the HSB operation for future generations. This constraint on the design parameters may also provide an opportunity to implement some advanced concepts, like the Lemprex, in their first real world trials.

The design of a Lempor exhaust is by no means arbitrary. Mathematical relationships derived from fluid mechanics as well as empirical testing require data to be input into equations so that the proper exhaust system proportions can be established. The same applies to the Master Mechanics spark arrestor.

The challenge of obtaining such data for 5906 was that any test program had to be worked into the busy timetable of the railroad and fit within scheduled service windows for the locomotive – such is the demand placed on their steam locomotive roster in 2014!

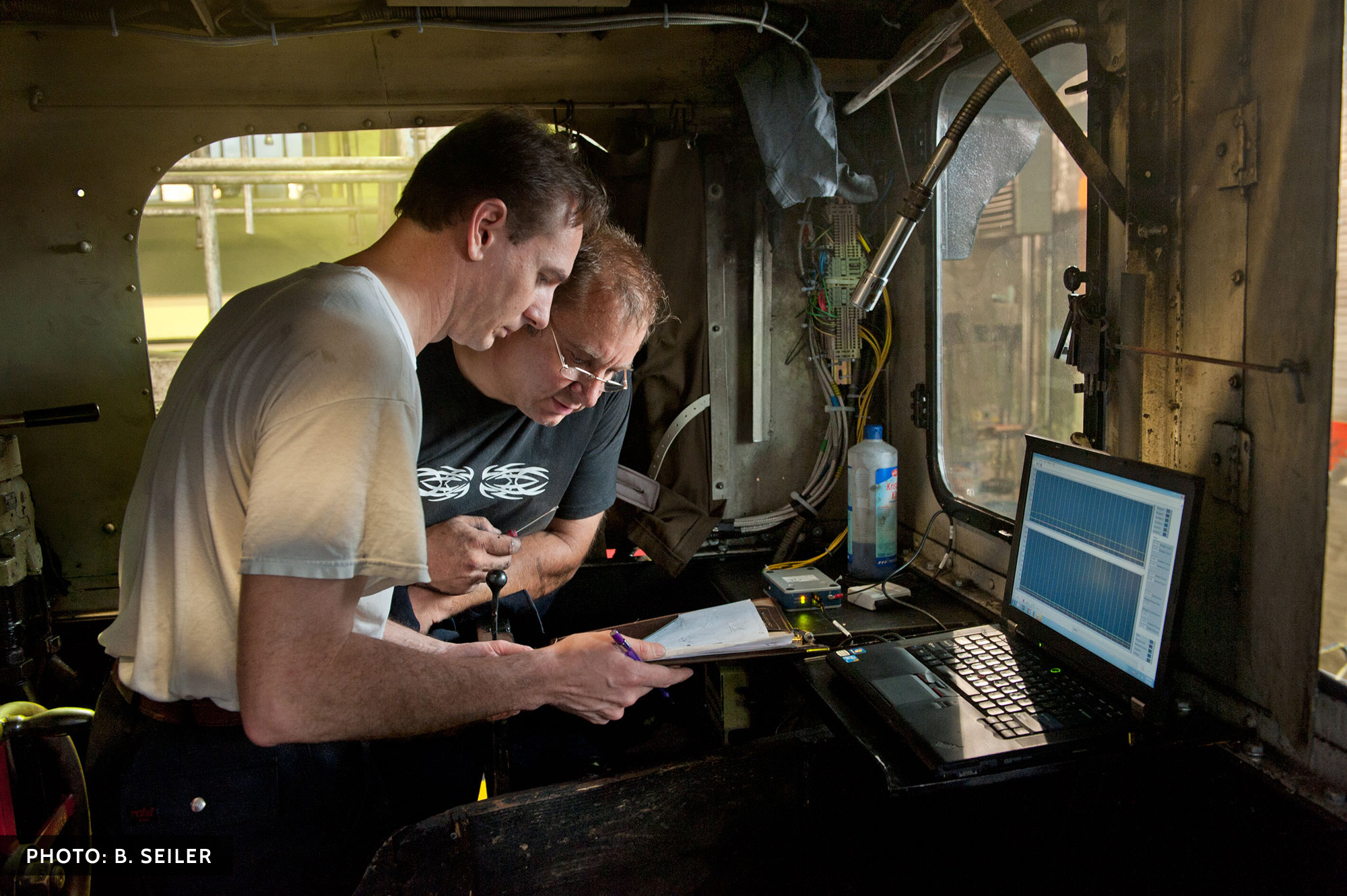

19th Century meet 21st Century- W. Fengler and H. Trieglaff compare notes in the Wernigerode Locomotive facility on July 30, prior to beginning test runs.

We finally had an opportunity at the end of July, leaving roughly a month to pull all the pieces together. CSR software and hardware engineer Nate Bolyard set to work coding up the program needed to read the data into the computer. Fortunately, a $25,000 grant from National Instruments had provided the specialized LabView software needed by Nate to accomplish his task. John Rhodes was kept busy ordering computer parts, sensors and other hardware specified by Nate and myself. I should note that CSR stays well ahead of the curve in planning terms (with backups thought out), but such is the nature of railroading that time is a luxury not always afforded us. I was very pleased to see how the team rallied together under these conditions and got the job done despite the circumstances.

19th Century meet 21st Century- W. Fengler and H. Trieglaff compare notes in the Wernigerode Locomotive facility on July 30, prior to beginning test runs.

Sunday, July 27, 2014

In the early morning hours, with my luggage crammed with thermocouples, pressure sensors, a laptop and other paraphernalia in addition to a week's worth of clothes, I headed out in the darkness to catch an 08:00 flight from Denver bound for Berlin. The connection through Newark came off without a hitch, but between the excitement and marginal seats in economy class there wasn't much in the way of sleep to be had.

Monday, July 28, 2014

The plane arrived on time at Berlin's Tegel airport at 08:00 Central European Time. After very little sleep and way too much time not moving, my first task was to make my way via bus to the Charlottenburg train station. This gave me a first opportunity to exercise my two years of high school German as airport signage to the bus loading area appeared to be non-existent. A conversation in German with a helpful airport worker gave me directions to the bus terminal. I managed to follow them reasonably well and found my bus. At the train station, I had enough time to enjoy the passing parade of S-Bahn, light rail, and ICE trains for a while before catching my own S-Bahn train to Magdeburg. The train action helped to detract from the hot, humid German summer and the trainshed provided welcome shelter from the occasional thunderstorm.

With a transfer at Magdeburg to a DMU trainset, I settled in for the last leg of my journey to Wernigerode. It was with one bit of consternation, however. While I had asked and been reassured in German that the DMU was bound for Wernigerode, there was a brief moment of concern as the train stopped at a station and then reversed direction; it initially appeared to be heading back for Berlin! Fortunately, moments later, it took a diverging track and continued on to Wernigerode, arriving on time at 14:30 where Bernd waited to welcome me.

Bernd and I drove directly to the HSB shops where I was introduced to the shop supervisor and the crew that had been assembled to install the sensors. Pre-trip coordination had determined the rough areas where the sensors needed to be situated, but the first order of business was to finalize their locations so the shop crew could get to work placing them when their shift started at 06:30 the next morning [LEFT]. I was pleased to note that the special cables for the sensors had already been roughed in, connected to terminal blocks, and batteries installed to provide 24 VDC power for the pressure sensors.

By the time all that was wrapped up, it was already 17:00. Bernd then guided me along the quaint side streets which would become my daily 5 minute walking commute from the hotel to the shops for the next week. After getting checked in at the hotel, Bernd left me to get settled in my room and to retrieve his car before joining me for dinner.

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Though I was not needed at the shop until 10:00, I still awoke at about my normal time. With a busy schedule ahead and the usual unpredictable nature of railroading, I took the precaution of finding a nearby store to pick up supplies of food and water in case "Murphy" came to call while we were out on the line, a wise bit of advice given to me by my Uncle Ross.

The rest of the day was spent answering questions about the sensors. This went better than expected given my rusty German and the unpracticed English of the one man on the shop crew who had taken English in school. A further complication arose in that not all of the special fittings required to install the sensors had arrived. Fortunately, the shop crew was able to improvise some alternatives which worked out just fine.

By the end of the shift, all of the sensors had been installed except the exhaust steam temperature sensor. During the day's work, it was discovered that there was an internal baffle in the steam pipe at the location we had identified for the sensor. I made arrangements to meet the crew at 06:30 the next morning to finish the work as we were scheduled to begin fire up at 13:00 and needed to have everything ready by then. I grabbed dinner at a café on the town square and headed off to bed.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

With fresh minds and an early start, we quickly settled on an alternative location for the temperature sensor and our resourceful crew finished their work while the electrician and I finished mapping out all the electrical connections from the sensors into the signal conditioning boxes so the computer could record the data. While the engine was building steam in the shop, Bernd and I had to head over to the engine shed to get ready for our afternoon with the locomotive.

One of our challenges over the next three days of testing was to be ergonomics. With the increased service demands, the 5906 and sister locomotive 99 5901 / 99 5902 are required to travel farther than they were originally designed to (180 kilometers between servicing as opposed to 30 kilometers). While there are plenty of water plugs along the line, coal is only available at the engine sheds. As can be seen from the picture of Bernd and me [BELOW], a wooden divider was constructed so that extra coal could be placed in the cab.

his meant, however, that for the first half of an 8 hour shift, I had to be tucked in behind the engineer, wedged into a narrow slot between the radio locker and wooden barrier so I could monitor the laptop. Indeed, part of the scheduling challenge was making sure that Bernd would be available to fire the locomotive since there was no way to get four crew members into the cab.

With little time available to debug the software with actual data from the engine under operating conditions, we headed out from Wernigerode on our scheduled train. I would have to get familiar with what the "normal" readings would be on the fly. Also, though I am trained in both US and metric measurement units, most of my engineering work in the past has been using US units, so I had to quickly develop a "feel" for the measurements.

View from the cab of a 2-10-2T at the Harz as it barrels through the mountains

It was quickly apparent that all the sensors, except one, were giving good data. What was odd were the boiler pressure readings. While Bernd did an excellent job keeping the pressure up, the value being displayed neither tracked the steam gauge nor aligned with its reading. That particular pressure sensor had been a last minute substitution due to a very long lead time of the unit we had originally specified and it covered a wider pressure range, so my first suspicion was incorrect scaling.

I did a number of calculations on the fly, but could not account for what I was seeing in the data. By this time in the afternoon, it was morning in Minnesota (seven hour time difference!), so I began a series of email exchanges with Nate Bolyard so we could debug the problem. By the time we reached the station at Drei Annen Hohne, we had a pretty good idea of what was going on. But we had to hand off 5906 to another crew at that point, so any solutions would have to wait until the next day. I grabbed the laptop and joined Bernd and our engineer for the day, Martin, in the cab of one of the 2-10-2Ts for the trip back to Wernigerode while another crew shuttled 5906 to Gernrode. A view from the cab of one of the HSB 2-10-2s along the line is shown at RIGHT. Gernrode would be our base of operations for the following two days as that run included the steepest grade on the line - a stretch of 4%. Back in Wernigerode that evening we put the locomotive to bed, cleaned up, grabbed some dinner and then some shut eye.

Thursday, July 31, 2014

The seven hour time delay worked in our favor. Overnight, Nate was able to fix one of the two problems we had identified the day before. I had not communicated the scaling of the replacement sensor to him so he needed to update the software. The updated software was waiting for me in my email first thing in the morning and our afternoon shift assignment gave me time in the morning to make the necessary updates to the laptop.

While we could have corrected the scaling problem during post processing of the data, it made life in the cab a lot easier when the sensor readings matched the gauge. The morning also brought confirmation of what the other problem was – a shut-off valve had not been opened when the steam pressure sensor was installed, thus the sensor was only reading whatever was trapped between it and the valve.

Bernd and I drove over to Gernrode and joined up with 5906 that afternoon. Much to our relief, the boiler sensor was now matching the gauge! Our joy was short lived, however, in that the exhaust steam temperature sensor was now reading maximum value – which told me that there was a short in that electrical circuit. A quick check of the cables, connections and sensor showed no signs of damage and as we had to keep to the schedule, there was no time to investigate any further. The rest of the afternoon and evening was fairly uneventful as we made two trips over the 4% grade. However, as our shift neared a close, we were held on a siding. As it turned out, one of the diesel railcars had an issue and this delayed our train by an hour (steam delayed by diesel). By the time we were serviced and tied down for the night it was 21:30 and we still had to investigate the problem with the temperature sensor!

The engine shed in Gernrode is only equipped for running service, so we had minimal supplies available. Using a volt-ohm meter, I quickly traced the problem to the temperature sensor itself. Fortunately I had brought a spare with us to Gernrode, but we still had to remove the sensor and install a new one. This involved removing the tack-welded metal shield which had been installed to protect the sensor given its close proximity to the road bed. With that out of the way, we removed the sensor [BELOW] and discovered that the sensing "beads" at the end of the thermocouple were sheared clear off – almost like they had been cut with a tool.

e concluded the most likely scenario was that the sensor had been vibrating in contact with the passage wall. Now the trick was to reinstall the sensor so it would be steam tight – with no teflon tape in sight! We improvised with electrical tape and some oil coated string as packing. We finished up sometime after midnight, cleaned up and then headed back to Wernigerode to try to catch some sleep.

Friday, August 1, 2014

With another afternoon shift lined up, I was able to spend the morning enjoying the shops of historic Wernigerode in search of a little something for my wife. Bernd and I again headed out to Gernrode to catch our afternoon assignment, hoping that our improvised thermocouple installation would hold. Much to our amazement, it did! In fact, sensors and software performed flawlessly for the entire day.

A good thing too, in that it was our last day of testing and Bernd had been left with a firebox full of clinker by the morning crew. With no drop grate, Bernd worked his tail off trying to break up the pieces and rebuild the fire, but he managed to keep up with things, a tribute to his firing prowess. We tied up in Gernrode that night and were met by a couple of guys from the shop who then removed the sensors and capped the sensor ports [ABOVE LEFT]. The wiring harness was left in place and sensors safely locked away for the next round of testing with the Lempor stack and Master Mechanics front end.

Saturday, August 2, 2014

It was hard to believe, but the week was over. Bernd was to drive me to Berlin as he had business to attend to there, but needed to catch up on work before we left. I spent the day packing, studying the 2-10-2Ts and Bernd arranged for me to get one more cab ride. That afternoon we drove to Berlin and enjoyed a nice celebratory dinner before Bernd dropped me off at my hotel near the airport.

Sunday, August 3, 2014

A long day of travel began with an 08:00 flight from Berlin to Frankfurt, then Frankfurt to Philadelphia, and finally Philadelphia to Denver. While I arrived in Denver at 21:00 as expected, my luggage took a detour in Philly – a good thing that didn't happen on the flight out!

Epilogue

With second-by-second data from our three days of testing in hand, I have assembed it so that our team can review the data and design both a new stack/nozzle and a master mechanic's front end. We will also be building a thermodynamic model of 5906 to use along with the data in proportioning the stack and recommending additional improvements which can be implemented over time.

Andre Chapelon and Dante Porta perfected most of their advanced technologies by improving existing locomotives. It is fitting that we are able to follow in the footsteps of our forefathers by advancing the art while ensuring the vitality of historic steam power. We extend our sincere thanks to Bernd and everyone at the HSB for being such wonderful hosts and providing this opportunity to CSR.